Building a Beta recovery in Asia

Nick J. Freeman, Associate Fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), considers some of the key challenges, old and new, that a post-pandemic K-shaped recovery may mean for DFIs in Asia.

The speeds and extent to which national economies return to some kind of normalcy post-pandemic will vary; a function of a range of factors, many of which existed pre-pandemic, that policy-makers and development partners will need to manage.

Asia is no exception – a K-shaped recovery is increasingly on the cards, whether viewed through the lens of differing performances of economies, sectors or even the size of companies. While large-scale firms have had some success in vaccinating parts of their supply chains, smaller firms are more vulnerable to new waves of infections. Some sectors, like tourism and hospitality, need to gird themselves for a long haul recovery, while others – such as agribusiness and soft commodities – can already see light at the end of the tunnel, and arguably experienced relatively few symptoms from the virus in 2020.

As a result, for DFIs operating in Asia, with a mandate to empower private sector actors in the developing world to address issues around poverty and income, the post-Covid economic environment will pose new strategic challenges. Like governments and the private sector, DFIs will need to lean into some of the changes that the virus has triggered, and not simply seek to row them back – think of the virus as Pandora, inviting us all to begin thinking outside the box.

Some of the change has been triggered by the pandemic itself, while other elements pre-date Covid-19 but have been accelerated and accentuated by the impact of the virus. For example, the kinds of advances in digitization (fintech, agritech etc.) that hold the promise of unlocking long-established MSME growth constraints have a provenance that dates back to well before 2019. Depending on one’s view about the potential, risk adjusted up- and downsides of the digital revolution for small-scale business development, this could become an exciting entry point for DFIs to bring about systemic impact (everyone would like to be a mid-wife at the birth of the next M-Pesa of the post-pandemic age).

Conversely, the kinds of supply chain dislocations that the pandemic unleashed in 2020 put wind under the wings of those already calling for protectionism and a pulling back of what were seen as overly-extended supply chains. Should it come to pass, a trend of greater ‘onshoring’ and ‘proximity sourcing’ could become unhelpful headwinds for those DFIs leveraging cross-border production networks as a means to support local input suppliers in Asian developing countries.

Furthermore, at a bigger picture level there is an existential question mark over the traditional East Asian economic growth model – the collegial notion of the ‘flying geese’ pattern of regional development is replaced by something more adversarial (dogfight by drones?). The worry must be that the value-added ladder that helped less developed and developing countries to advance up the value chain could be steadily pulled away by innovations in manufacturing, and even agribusiness. These are innovations that have proven not only immune to COVID-19, but to have actually fed off the pandemic in some ways.

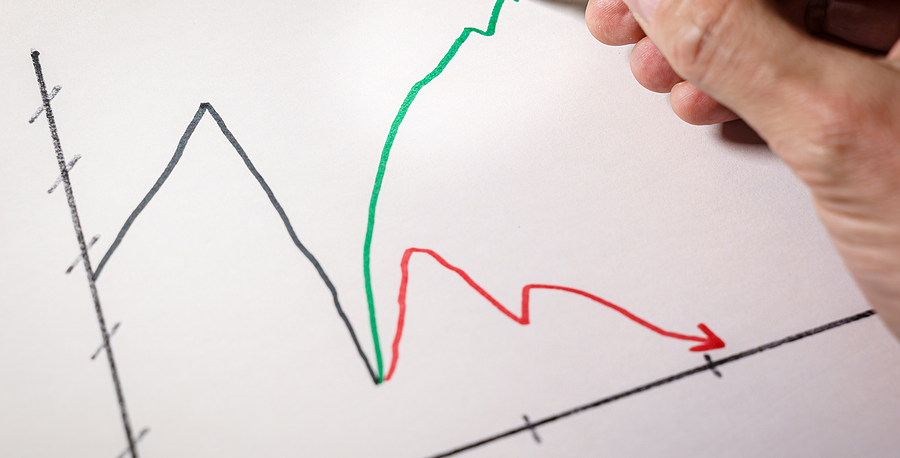

But for DFIs with a different mandate to institutional investors, notably in terms of impact return, asset allocation will need to be more nuanced. And it is amongst the developing and less developed economies of Asia where things seem much less certain, given their limited institutional capacity and funding to conceptualise, design, implement and enforce effective COVID-19 response and all-important recovery measures that are sustainable in the long-run. (There has to be some concern that the emergency mitigation and recovery measures enacted over the last year may trigger an ersatz dead cat bounce in 2021 – the ADB is forecasting 7.3% GDP growth for developing Asia in 2021 – that cannot be sustained.)

A K-shaped recovery in Asia suggests that economic growth prospects will likely bifurcate along the same fault lines that demarcate economic and prosperity fault lines in the region. It could also mutate into greater political risk issues, as elements of society already badly bruised by the Covid-19 experience start to attribute blame. A widening of the income divide, between the more affluent and the least developed economies, in Asia and elsewhere, is something that the IMF and others have begun to raise as a source of valid concern. Today’s GDP contractions are tomorrow’s rising poverty levels.

Some cautious optimism can be derived from the fact that the pandemic has not derailed growing calls for sustainability, and the need to address increasingly pressing climate change issues in Asia. If anything, the pandemic has felt to some like a message from ‘Gaia’ that the sustainability agenda remains the principle prize on which DFIs need to keep their eyes firmly focused. This is clearly not the time for the DFI community to blink.

If Covid-19 was a mindful moment, and the resources applied to economic recovery were made to align with a more inclusive and green development agenda, then DFIs will have a key role to play in intermediating that policy agenda with the capital and technical expertise that resides in the private sector.

About the author:

Nick Freeman is an economic development consultant, currently based in the Bay Area of the US. From 2002 to 2011 he was in Vietnam, and from 2011 to 2018 he was in Myanmar. Nick has also worked on projects in Bhutan, Cambodia, Laos, Singapore and Thailand. Until 2018, he was Director of Investments at the DaNa Facility in Myanmar, and currently leads BAF II – a multi-donor funded matching grant fund in Laos. Nick holds a PhD in International Business from the Univ. of Bradford.