Which African sovereigns are most likely to default?

Since the start of the pandemic only two African countries have defaulted on their sovereign debt, in large part because of remedial action by multilaterals and DFIs. But the potential for default continues to grow. Robert Besseling, CEO of PANGEA-RISK, looks at possible African state default scenarios for the next five years and, by extension, where future debt relief initiatives might have most impact.

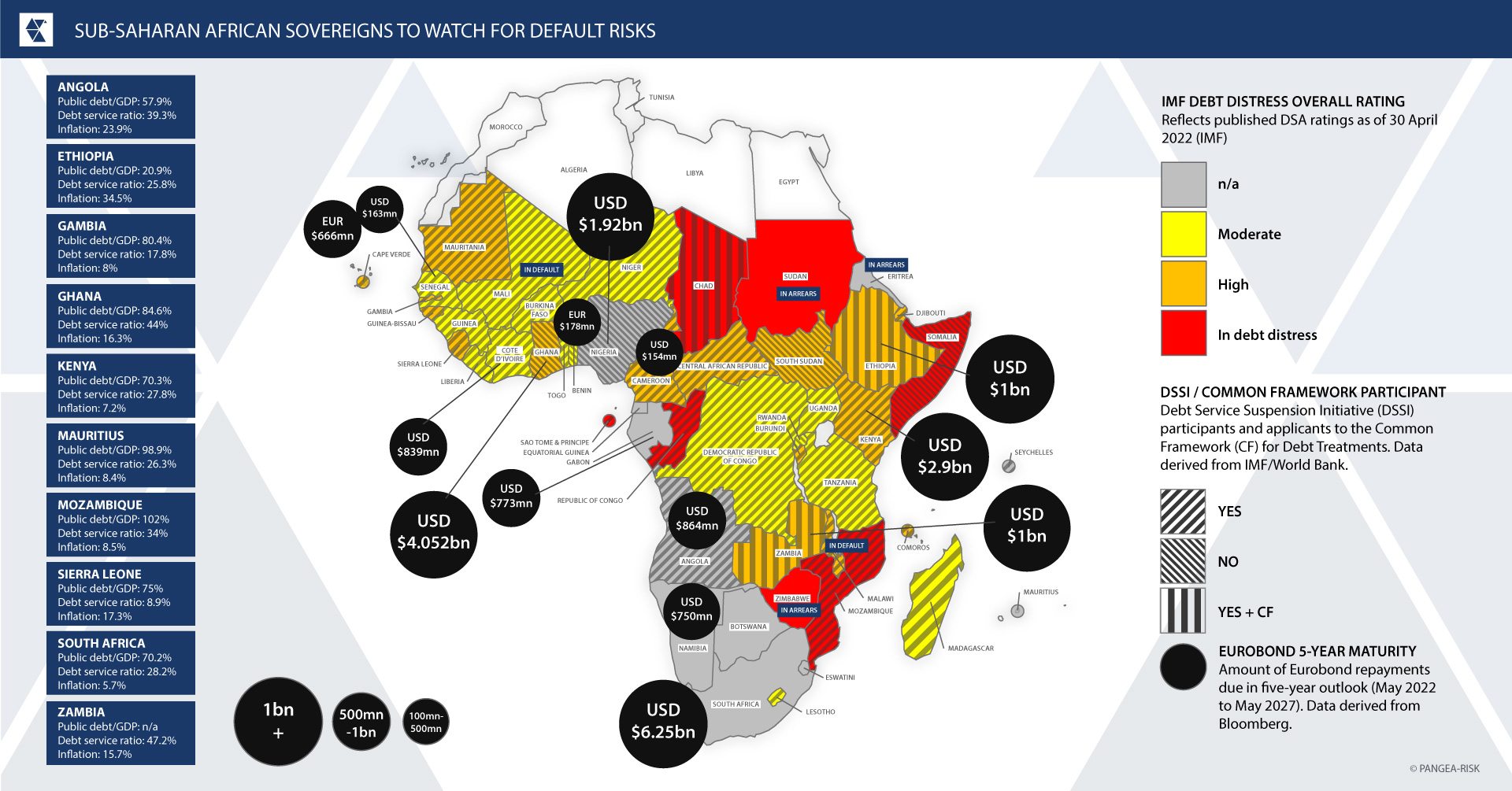

Over the next five years, several already debt distressed African countries are due to make sizeable repayments on their foreign currency denominated sovereign bonds, even while rising inflation, slowing economic growth, and depleting foreign exchange reserves put pressure on their own local currencies. PANGEA-RISK has identified the most probable default scenarios over this period, including in large African markets such as Ghana, Kenya, and Ethiopia.

Since the start of the pandemic over two years ago, only two African countries have defaulted on their sovereign debt, namely Zambia in late 2020 and Mali in early 2022. Remedial action by multilateral financial and development institutions have so far mitigated a wider debt default. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank are now seeking more ambitious initiatives to offer debt relief and loan restructuring for low income countries.

Sovereigns at highest default risk

With the expiry of the debt service suspension initiative (DSSI) at the end of last year and the low uptake of the Common Framework, there is mounting concern that low-income countries will not be able to meet their $35 billion in debt payment obligations this year. The IMF now rates 23 countries out of 50 sub-Saharan African states to be in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress, which is up from just eight countries in 2015. Without bolder debt relief or further special drawing rights (SDR) issuance, several African countries are set to default in coming years, including Ethiopia and Tunisia, as well as perhaps Kenya and Ghana.

In the five-year outlook (May 2022 to May 2027), several sub-Saharan African countries are due to make $21.5 billion in repayments of Eurobonds, excluding the cost of servicing these foreign currency denominated loans. These include heavy borrowers such as Ghana. which owes more than $4 billion to bondholders between now [June 2022] and May 2027, and Kenya, with a bond repayment bill of almost $3 billion for the next five years. The debt sustainability outlook of the continent’s largest economy, Nigeria which owes almost $2 billion in Eurobond repayments, is also becoming more concerning. While Ethiopia has only one Eurobond, a $1 billion bond due in 2024, it is becoming increasingly improbable that the conflict-ravaged country will be able to repay the capital in two years, let alone service the loan in the meantime.

Rising cost of debt

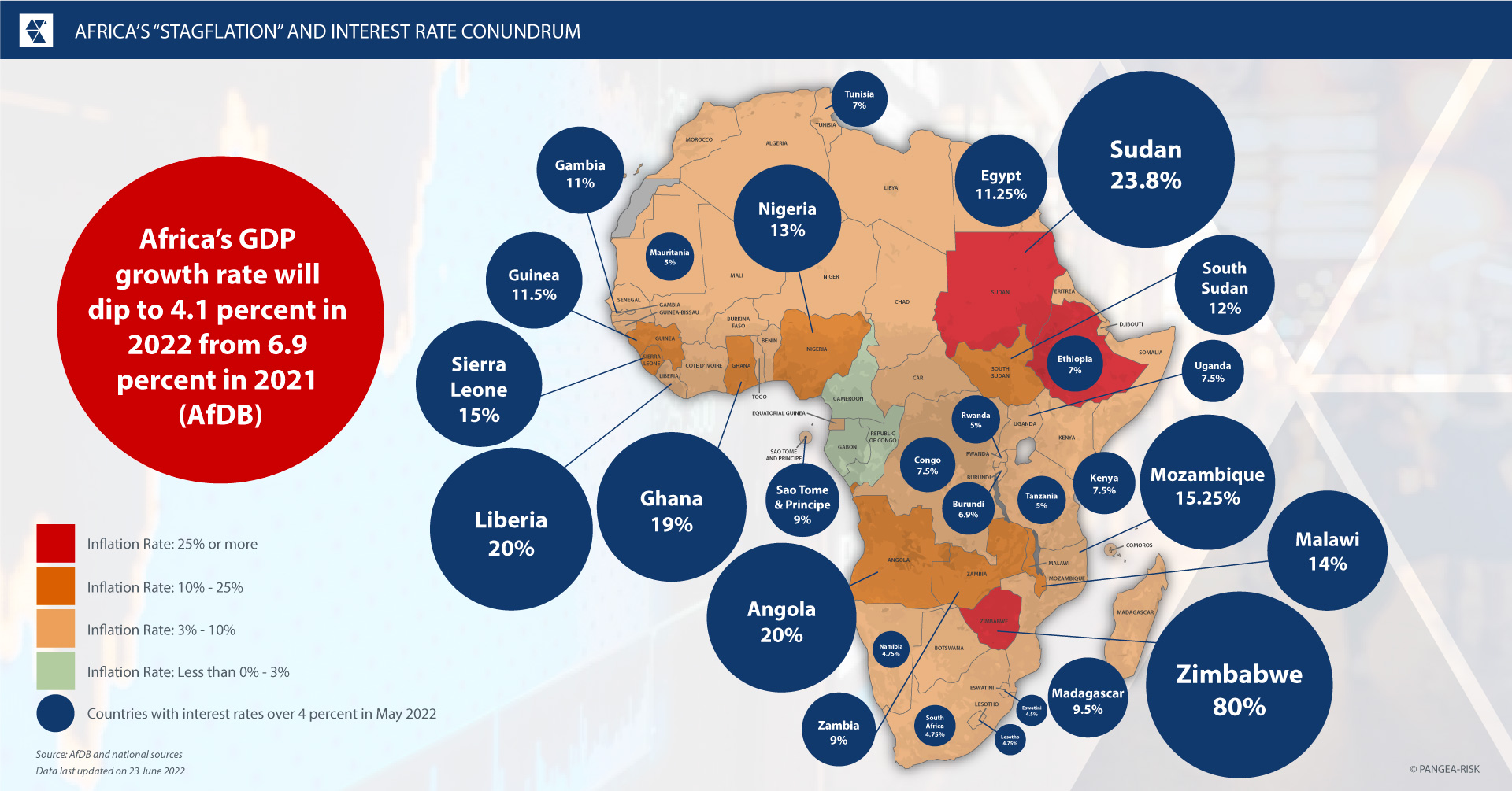

As the cost of debt servicing increases – it tripled between 2010 and 2021 – African sovereigns will struggle to meet regular interest payment deadlines. In the first two years of the pandemic, interest rate cuts by big central banks made it relatively cheap for governments to borrow. But with global monetary conditions tightening this year, it is becoming more expensive to refinance existing debts. African economies seeking to borrow on the international markets could be in difficulty if the US Federal Reserve rates are increased more than anticipated. Higher-than-anticipated US rate hikes could prompt significant capital outflows and put pressure on central banks to increase the price of domestic credit, potentially dampening growth.

Zambia defaulted on a Eurobond interest payment in late 2020, while Mali has stopped servicing and repaying its West African central bank (BCEAO) held debt due to regional sanctions. Rising US interest rates and tumbling currencies will increase the debt-to-GDP ratios, while raising the cost of borrowing. Countries already in arrears and with large debt burdens, such as Sudan, Eritrea, and Zimbabwe, will see their debt increase even more. Higher interest rates also means that countries such as Ghana will no longer be able to affordably tap into international debt markets to refinance existing debts. Several large markets such as Angola and Kenya are already scrapping plans to issue more Eurobonds this year, while others like Nigeria are issuing debt at costly interest rates, rendering their debt profile less sustainable.

Meanwhile, the total value of debt repayments is rising. In 2022, the world’s poorest countries face a $10.9 billion surge in debt repayments. This increase in debt repayments comes as many African countries shunned the DSSI, which was launched by the G20 group of large economies in April 2020 and aimed to defer about $20 billion owed by 73 countries to bilateral lenders between May and December 2020. Despite being extended to the end of 2021, just 42 countries globally received relief totalling $12.7 billion, according to the Paris Club group of creditor nations that helped coordinate the initiative along with the World Bank and the IMF. Those countries must now resume repayments this year and start recognising debts that were suspended under the scheme.

Eurobonds at higher non-payment risk

Eurobonds are not the only financial obligations for African countries, which will need to make a total of $185 billion in loan repayments between 2022 and 2024. Most African states have borrowed commercially from banks and export credit agencies, bilaterally from other governments, concessionally from development banks or multilateral financial institutions, or from Chinese state-controlled entities. However, a default event is more likely to occur on a Eurobond tranche payment or capital repayment, than on any other form of obligation.

Zambia has continued to make payments to the World Bank, some banks and ECAs, and Chinese entities, even while ceasing to pay interest due on its sole external bond. Even though Eurobond structures may not always be more onerous in terms of servicing cost, they are complex to restructure, while the broader socioeconomic and political implications of stopping or delaying payments to China or development banks are often far more serious.

PANGEA-RISK has therefore devised a quantitative methodology derived from data from multiple sources to review individual sub-Saharan African countries’ debt profiles and loan servicing ability, as well as their respective external bond repayment obligations in the five-year outlook. Many emerging markets will require at least five years to recover from the triple shocks of the pandemic, Russia-Ukraine war, and broken supply chains, which justifies our chosen timeline for this assessment.