Shop talk: Where’s climate finance at?

With COP27 on the horizon, Uxolo spoke to Pedro de Aragao Fernandes, analyst at Climate Policy Initiative to outline one of his co-authored reports, the Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021 – the leading source of climate finance tracking on public and private sources.

Uxolo: Could you introduce the landscape of climate finance at the moment, especially in regards to funds that are being directed towards developing economies?

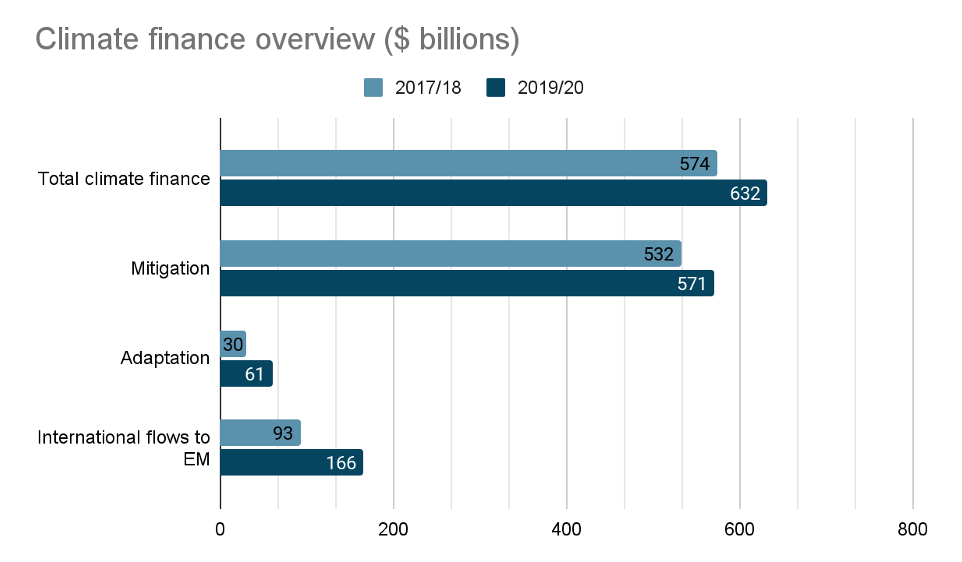

Pedro de Aragao Fernandes (PF): Global climate finance flows reached $632 billion (annual average) in 2019/2020, a 10% increase from 2017/2018. While public and private actors have steadily increased their climate investments in the past decade, these flows have slowed in the last few years. This is worrying because COVID-19’s impact on climate finance is still yet to be observed. The vast majority (90%) of tracked finance continues to flow towards activities for mitigation, while the remaining 10% flows to both adaptation projects and projects with dual benefits (mitigation and adaptation).

Pedro de Aragao Fernandes (PF): Global climate finance flows reached $632 billion (annual average) in 2019/2020, a 10% increase from 2017/2018. While public and private actors have steadily increased their climate investments in the past decade, these flows have slowed in the last few years. This is worrying because COVID-19’s impact on climate finance is still yet to be observed. The vast majority (90%) of tracked finance continues to flow towards activities for mitigation, while the remaining 10% flows to both adaptation projects and projects with dual benefits (mitigation and adaptation).

Regions where the majority of low-and middle-income countries are located received less than 25% of climate finance flows and are mostly dependent on international climate finance flows. Climate projects in the economically advanced regions of Western Europe, the US and Canada, and Other Oceania were primarily funded by private finance, while the rest of the regions sourced their climate investments mostly from public sources. All regions mainly funded mitigation actions, with 80% of the mitigation investments concentrated in the high emitting regions of the US and Canada, Western Europe, and East Asia and Pacific. These regions also received high shares of domestic flows, accounting for 76% of the global flow. Inversely, a higher share of international finance was observed in the developing regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, the majority of which were directed towards projects with cross-sectoral impacts and those related to energy systems, AFOLU and fisheries.

Source: CPI Global landscape of climate finance 2021, 2019

Uxolo: As COP27 will have a special focus on Africa, could you go into more depth on the continent’s climate finance figures and initiatives?

PF: In our recent publication Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa, which covers 2019-2020 climate finance, CPI estimates annual climate finance flows in Africa stand at $29.5 billion. Most of this climate investment is from public international actors (80%) and private sector finance (14%). Contributions from African Governments (4%) remain largely unreported due to insufficient tracking of domestic climate budget expenditures. Africa strikes a better balance between adaptation and mitigation than other regions. Mitigation accounted for 49% of climate finance flows, followed by 39% towards adaptation, and 12% to dual benefits. This is a positive trend, given Africa’s disproportionately high vulnerability to climate change. Yet funding for both adaptation and mitigation must still increase by at least 6 and 13 times, respectively.

Uxolo: What is the public-private capital relationship in the global climate finance space, and what roles are these investment groups taking on?

PF: These groups are almost evenly weighted in terms of investment amounts. Public actors provided 51% ($321 billion) of annual climate finance in 2019/2020, an increase of 7% compared to 2017/2018. While private climate investments increased by 13% in 2019/2020 compared to 2017/2018, their share of total climate finance fell from 56% to 49% ($310 billion).

All public sources are increasing finance, but their roles are evolving. National development banks continue to support domestic energy sector projects, but the majority is now going to the transport sector. Governments played a prominent role in the transport sector at the beginning of the decade and this role is strengthening in recent years through grants and subsidies aimed at increasing the uptake of lower emission vehicles among consumers. The role of climate funds is more prominent in catalysing and coordinating resources for co-financing, including at national levels.

Private actors’ contributions are increasing, but not at the pace necessary considering public sector capacity constraints. Private finance is driven by corporates, commercial financial institutions, and households. Corporate entities provided the largest share of private climate finance; however this has declined to 40% from 57% previously. Greater access to debt financing from banks is allowing corporations to reduce the amounts financed through balance sheets. Corporates allocated 75% of their climate finance into renewable energy projects and 20% into low-carbon transport projects.

Commercial financial institutions are now the second largest source of private climate investment, accounting for 39%.Their more prominent role explains the increase in climate finance as financial markets moved into sustainable industries – particularly energy systems, which received 82% of banks’ climate finance in 2019/2020.

Households remain the third largest share of annual climate finance, where spending increased to $55 billion in 2019/2020, and was directed to electric vehicles and small-scale solar panels.

Climate finance from institutional investors remains comparatively low, at 1% of the total, and mainly focused on renewable energy assets. This is due to several barriers including low risk appetite, a need for larger project sizes, and a lack of policy incentives.

Uxolo: Private investors are seemingly comfortable investing in climate mitigation projects, particularly traditional renewables. What's driving this comfort? And where can we expect private investments to flow next?

PF: Renewables were primarily financed through private capital. Solar PV and onshore wind continued to be the main recipient of renewable energy finance, attracting over 91% of all mitigation investment. This trend reflects the sector’s growing commercial viability, where efficiency gains and cost reduction of renewable energy technologies have established high and low-risky financial returns, attracting interest of the private sector.

Corporates representing established energy utilities, independent power producers, and project developers specializing in renewable energy represented the largest single class of investors historically. Their composition is now gradually diversifying whereby non-energy related corporates and commercial financial institutions are joining the efforts to combat climate change.

To use Africa as an example, there is huge potential to translate the continent’s sustainable energy needs into investment opportunities and reduce investments in fossil fuels. Africa will need around $133 billion annually in clean energy investment to meet its energy and climate goals between 2026–2030, according to IEA, 2022. However, annual investment in renewable energy — arguably the most attractive sector for commercial investors — stands at a mere $9.4 billion. This is a fraction of the continent’s investment in fossil fuels which is about $29 billion per annum between 2016–2021, and government subsidies for fossil fuels which stand at $37 billion per annum in 2019/2020, according to Banktrack, 2022.

Uxolo: Data has not yet been released or completed for the 21/22 period but would you say that there have been any significant changes in trends that you have noticed?

PF: What I can say now is that private sector investment is increasing, but not at the scale and speed necessary for the transition. Private sector actors, particularly financial institutions with trillions of assets under management, are committing to net zero and the sustainable finance industry is gaining traction. Nonetheless, the rate of growth of private sector climate finance in the most recent years was slower than that of the public sector; their scale needs to increase rapidly.

The public sector has played an active role in channeling finance to hard-to-invest sectors such as agriculture and adaptation. Moreover, they were particularly crucial in scaling renewable energy investment by supporting and enabling technology cost reduction, as well as providing revenue support mechanisms to attract more private flows.

Finance towards renewable energy made the most progress whereas other sectors have lagged significantly. The renewable energy sector was transformed into an established and competitive sector with a 7 times higher return on investment than fossil fuels, according to IEA, 2021. Transport is the fastest growing sector, while other critical sectors including agriculture, forestry, land use, water and wastewater are trailing behind. Most importantly, adaptation finance has been significantly underfunded.

Uxolo: Finally, would you say that the current amount of climate finance is meeting global need?

PF: We are nowhere near enough. Global climate finance has almost doubled in the last decade – but the current levels of increase are not on track to a 1.5C global warming scenario.

Multiple paths exist to cut anthropogenic GHG Emissions and available scenarios explore various alternatives, from concentrating mitigation efforts in specific sectors to banking on technical innovations. These different options result in a wide range of estimates. Total annual investment needs in mitigation and adaptation solutions sit between $3.8 trillion and $7.8 trillion on average through 2030. When looking at the 2021-2050 period, annual needs could reach even higher levels, from $5.1 trillion to $11.2 trillion, as certain technological breakthroughs are included in some scenarios.

In regards to Africa, CPI estimates that the continent needs $277 billion annually to implement its NDCs and meet 2030 climate goals. But annual climate finance flows in Africa stand at only $29.5 billion. This gap is likely even wider as countries often underestimate their financial needs, especially in relation to adaptation, due to data and methodological problems in costing their NDCs.

Climate finance is a small share compared to overall stock and investment in high emissions and business as usual activities. This is alarming as fossil fuel subsidies are only a part of overall funding in high emitting activities. Immediate action to remove dependencies on fossil fuel including harmful subsidies will free up resources for more sustainable investments as well as improve consumer price stability and increase energy independence.

Furthermore, data on finance flows is improving, but less is known about the impact and outcome of deployed climate finance. Public international climate finance is advancing on its reporting methodologies, which enables providers to better understand and prioritise climate investments. However, the same level of sophistication and consistency in reporting is lacking from the private sector, and from public domestic budgets, which leads to data gaps in climate finance and, more broadly, knowledge gaps in understanding the levels, impact, and effectiveness of climate finance.