Quick to promise – slow on delivery again

COP26 featured renewed pledges to deliver on past undelivered financial promises, spawned a number of new grand support schemes and turned up the volume on calls for the levelling up of climate finance. With COP27 fast approaching, this time specifically focused on Africa, what has actually been achieved in funding terms in the 12 months since the last COP?

FMO’s director of partnerships for impact, Idsert Boersma, sums up many peoples opinion on COP: “Even if the last one was not successful”, says Boersma, “conversations happen because COP is there”. COPs serve a useful bridging function between NGOs, governments, DFIs, and private investors. The events even hold governments publically accountable for their climate pledges – the failure to meet the $100 billion promise in annual climate financing to emerging markets was recognised as a breach of trust at COP26.

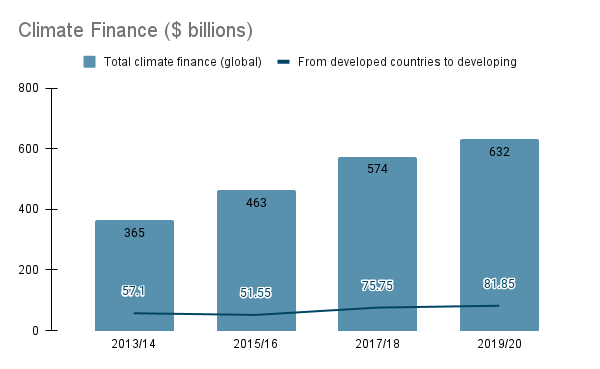

While COP is a useful platform for highlighting problems, it is relatively toothless when it comes to biting the global political elite on the regulatory backside. For example, the OECD predicts the $100 billion pledge will remain unmet until at least 2023. And although climate finance has doubled in the last year, Climate Policy Initiative told Uxolo that even current levels of increase are not on track for a 1.5C global warming scenario.

So, given its limitations, is COP really a platform for change or a platform for chatter? The proof is in what has been delivered on proposals made at COP26.

COP26’s private investment initiatives

MCPP One Planet, three vehicles managed by IFC, HKMA, and Allianz, was launched at COP26 with a plan of directing up to $3 billion in climate smart investments towards private enterprises in developing markets. A year on, Nadia Nikolova, lead portfolio manager at AllianzGI Development Finance, told Uxolo that the aggregate vehicle was able to achieve this promise in interested investor capital and that detailed disclosures were due to be released at COP27.

Another commitment was made by IFC and Amundi which launched the $2 billion Build-Back-Better Emerging Markets Sustainable Transaction strategy designed to channel capital from institutional investors into anchor investments in sustainable bond issuances from corporates and financials in developing countries. Amundi is managing the fund and Eric Dussoubs, senior institutional clients coverage at the firm, told Uxolo that the strategy was still in its fundraising stage but the progress being made was “fantastic”.

A third initiative came from CIF’s capital market mechanism which planned to boost investment into clean energy in developing countries. Bonds were due to be issued in 2022 in London, expecting to mobilise $700 million annually, but, a year on, there have been no public updates on the progress of this initiative and the World Bank group declined to comment.

GFANZ, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero, was one of the biggest tickets launched at COP26 with its signatories holding approximately $1.3 trillion AUM. Its criteria requires members to set science-based 2050 net-zero goals, interim 2030 goals that represent 50% of the way toward net-zero, and to follow transparent carbon accounting and restrictions on offsetting.

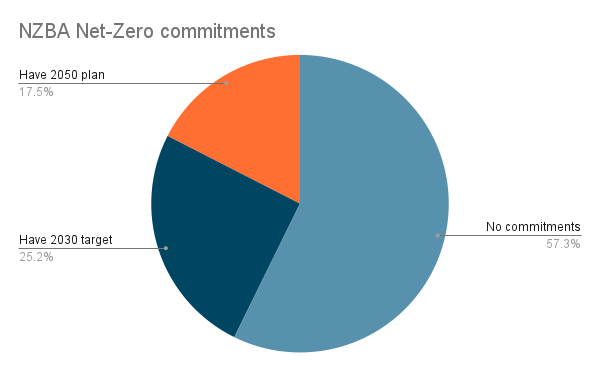

Membership of the GFANZ Net-Zero Bank Alliance has increased over the last year – however, of the 85 total signatory banks, only 26 have a 2030 target and 18 have a 2050 transition plan. Meanwhile, UK campaigners have highlighted the estimated $8.7 billion HSBC has invested in new oil and gas in 2021, the $4.5 billion from Barclays, and $5.7 billion from Deutsche Bank, despite these banks having NZBA membership and IEA stating there should be no new oil or natural gas fields. GFANZ has also suffered setbacks with the departure of pension funds Cbus and Bundespensionkasse and the threat of some big-name US banks leaving (a rumour since denied by Mark Carney), citing risks of lawsuits under SEC rules if they introduce the stringent transition policies.

Source: Banktrack 2022

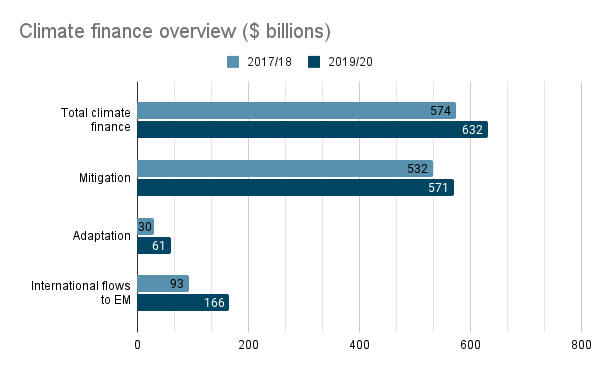

In sum, excluding AUM, these widely publicised COP26 initiatives amount to under $6 billion so far – nowhere near the $1 trillion needed. Ultimately, the conference has been unable to catalyse the private investment it craves: “Private sector investment is increasing, but not at the scale and speed necessary for the transition. Private sector actors, particularly financial institutions with trillions of AUM, are committing to net zero and the sustainable finance industry is gaining traction” summarised CPI senior analyst Pedro Fernandes, “nonetheless, the rate of growth of private sector climate finance in recent years is slower than that of the public sector; their scale needs to increase rapidly.”

Delving deeper into the figures, it is clear where private capital is flowing. CPI shows that corporate entities accounted for 40% of private climate finance in 2019/20. Of this amount, 75% was directed towards renewables, and 20% low-carbon transport. The second largest player was commercial financial institutions which accounted for 39%; again, 82% of these bank’s investments were directed towards energy systems. Overall, 91% of private climate capital went towards renewable energy, and as Fernandes notes, it was the commercial viability of the sector that caused its popularity – efficiency gains and cost reductions have evolved the sector to a point of low-risk, market-rate returns.

However, at Uxolo’s recent global conference, one speaker highlighted that getting funding even for traditional renewables in emerging markets remained difficult due to the abundance of bankable alternatives in Europe and North America. According to Uxolo’s data, even the majority of development finance capital is directed towards Europe – Africa receives the second most, around $4 billion less. Boersma also highlighted two lingering issues: the difficulty of finding business solutions for climate adaptation, and the continuous debate around the just transition. He argues that ensuring social stability alongside climate investments is a flipside of the same coin, and that projects that fail to address both issues simultaneously are not worth investing in.

The need for structure

Last year, Uxolo’s Oliver Gordon interviewed Dr Olaf Weber at the University of Waterloo, who stated that “compared with what we had with the Kyoto agreement in 1992, which was a very structured financial mechanism, we didn’t get anything like that in Glasgow”. Weber was referring to the financial mechanisms introduced at the first COP, the carbon trading market, which aimed to fold negative externalities back into the market by assigning property rights to GHG emissions.

Bella Tonkonogy, director for CPI and member of the GFANZ advisory panel, highlighted the importance of structure, you need something “that not only tells them they’re not doing enough but that also says here’s a support structure with protocols, methodologies, and some ambition to help you actually do what you need to”. In fact, she was not referring to private capital but public, following a recent report by CPI revealing the surprising deficit in public institutions’ net-zero commitments. Of 71 tracked public institutions representing 95% AUM ($20.4 trillion), only 25% of assets were subject to net-zero targets. Outside of the MDBs, very few public bodies including ECAs, national and subnational banks, mortgage securitisation and public housing agencies, had made commitments to align their operations with the Paris Agreement and even fewer had set targets specifically for their portfolios, which it is estimated where 97% of emissions are found.

The two worst performing institutions were ECAs and national development banks. Tonkonogy commented that ECAs had been facing pressure to stop investing in coal for years, and while some had stopped last year, the sector as a whole had a lot more to do “proactively” – “by and large they do not have targets or comprehensive climate strategies”. Of the 37 tracked NDBs, 33 belonged to countries which had net-zero commitments, but only four of these banks had their own commitments – “most of them have not even gone as far as their government”, said Tonkonogy.

Asked if the report should be addressed at COP27, Tonkonogy argued “Absolutely. It’s a no-brainer that you have governments that have committed to the Paris Agreement yet their public financial institutions, which they by and large control by definition, have not made the same commitments”.

The Uxolo perspective

At a recent impact investing forum, investors seemed to agree that climate change had fallen into a market gap; that, to a degree, financial markets needed to evolve to meet this problem. If someone asked what the odds were that individual, isolated private climate finance initiatives would scale up to the amount needed, the response would be pessimistic.

However, this perspective undermines the growing motivation of, not all, but a great many institutions to address the issue. Boersma mentioned one of the highlights from the last COP he attended, saying, “it was great to see big-name private investors, pension funds, big insurers, really interested in what DFIs were doing. They wanted the opportunity to learn; about technical asset allocations, about how they could step into tiny countries in Africa and Asia etc”. As Tonkonogy showcases, “where we have largely focused so much on private financial institutions, for good reason as their volume of assets is so large, … the climate community needs to pay more attention to the public finance sector”.

COP needs to construct consistent, bankable incentives for private capital to go where it needs to – through regulation, by encouraging risk-taking first losses (that can mobilise a 1:39 public to private capital ratio), by encouraging DFI and MDB collaborations with governments that can reduce credit risks, and by bridging the gap between public and private understanding with the help of data (such as by opening up the GEMs database, which Boersma stated was long overdue). If the conferences are a chance for global decision-makers to reconvene, gather their wits and show accountability, the result of these events needs to be (i) actual accountability and (ii) tangible, comprehensive strategies that capture as much capital as possible: private and public.