Singrobo-Ahouaty: A small hydro IPP ripple effect in sub-Saharan Africa?

The 44MW Singrobo-Ahouaty hydropower project is a pathfinder – the first hydropower IPP to reach financial close in West Africa. While the probability of a rush of similar private small hydro projects is unlikely, all the signs bode well for a growing niche with access to DFI liquidity.

Access to electricity in Africa is the lowest in the world – 43% of the population lack access, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa), where per capita consumption of energy is 180 kWh, compared to 13,000 kWh in the US and 6,500 kWh in Europe.

Ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for the continent (SDG 7) requires approximately $160 billion of investment per year. Concurrent with that, existing subsidy schemes designed to keep prices low for traditional fossil fueled power face the looming danger of price spikes as energy demand grows. For nations already tackling debt distress, such an outcome is untenable.

All African countries are signatories of the Paris Agreement and are looking to attract increasing flows of climate finance and renewable power, and hydro as a concept comes with some significant pluses. According to Paromita Chatterjee, fund manager of PIDG company Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund (EAIF), “once hydropower is constructed it provides cost efficient clean power which could last up to 50 years”.

But although Africa has the largest untapped potential for hydro, compared with other energy infrastructure sectors the market remains small (just 17% of electricity generation on the continent). The costs and risks of hydro projects have often been underestimated while benefits have been overestimated. Dams curtail natural river flows, potentially causing unexpected and irreversible ecological, socioeconomic, and political consequences. The necessary environmental studies take at least two years to complete, with at least a year to study the wet and dry seasons and at least a year to write up the plan. The preparation and design stage not only requires experienced contractors but also has the potential to drive up project costs drastically, especially if there are ecological or human risks that need to be avoided.

Africa has seen a proliferation of IPPs in the last decade, but the specialisation required of the hydro market has meant only three sub-Saharan countries had private hydro IPPs reach COD between 2000-2017 (excluding cancelled projects).

Hydro IPPs in sub-Saharan Africa 2000-2017

Country | COD | Total investment (millions, $) | Capacity (MW) |

Madagascar | 2007 | 17.8 | 15 |

Uganda | 2007 | 860 | 250 |

“ | 2009 | 65.7 | 13 |

“ | 2011 | 14 | 6.5 |

“ | 2011 | 27 | 18 |

“ | 2012 | 27 | 9 |

“ | 2016 | 18 | 5 |

“ | 2017 | 18 | 5.4 |

“ | 2017 | 18 | 5.4 |

“ | 2017 | 14 | 6.5 |

“ | 2017 | 34 | 9.2 |

“ | 2018 | 48 | 21.5 |

Angola | 2008 | 45 | 16 |

Source: World Bank

The first hydro IPP in West Africa

The recent Singrobo-Ahouaty hydro deal reached financial close in December 2022. Themis began the project in 2013 and the deal reached a bankable level within18 months, AFC consequently arranging a $160 million bridge loan in 2014 to kickstart construction while awaiting long-term lenders to secure their final credit approvals.

The project comprises design, development, operation and transfer of a 44MW hydroelectric plant on the Bandama River and a 3.5 km transmission line and substation to evacuate the power generated onto an existing transmission line.

The long-term financing closed in December 2022 with AfDB as mandated lead arranger. The project was financed with a 75:25 debt-to-equity ratio with AFC, AfDB, DEG, and EAIF providing the debt. AfDB committed €40 million on a 15-year tenor while AFC provided €40 million, DEG provided €25 million and EAIF provided an additional €25 million, all on an 18-year tenor. Equity made up €44 million of the financing and was provided by the project’s shareholders AFC (51%), Themis (35%), and Ivoire Hydro Energie (IHE) (14%).

The €174 million project was forecast to take 36 months to build and the plant is currently at 65% construction due to the bridge loan from AFC. A long-term PPA will see all of the energy produced by the Singrobo plant sold to Compagnie Ivoirienne d’Electricite, the operator of Cote d’Ivoire’s national grid.

Whilst markets are relatively comfortable allocating risk for solar and wind projects, the risk for hydro remains case specific – especially when considering hydrology risk. As Chatterjee says, “Ultimately, hydropower depends on hydrology. In parts of Africa, with climate change too, there are dry spells and sometimes the rainfall levels are too high, and that can bring additional risk to the project and communities up or downstream”. But, the Singrobo plant was built on a river that already hosts two large state-owned hydroelectric dams. As such, the water flow is managed by the state, therefore putting the hydrology risk in the public domain.

The other portions of risk – currency, political, and payment – were similarly allayed, mostly due to the project’s location. Cote D’Ivoire is comfortable guaranteeing the exchange rate of the CFA franc with euros, and political risk is not seen as a major issue as the nation has 30 years of track record with global investors since its first private power plant in 1994.

Where Themis has similar projects underway – in Madagascar and Chad – it has arranged partial guarantees with AfDB covering the first six to 12 months of payment, protecting it against the risk of the utility not paying the bill. The track record of Cote d’Ivoire and the creditworthiness of its electricity sector did not justify such a guarantee being put in place for Singrobo.

Marc Mandaba, co-founder and chief investment officer of Themis, says that a major risk of hydropower projects is environmental and social. Ecological concerns on Singrobo-Ahouaty included financing a new zoo area to house resident critically endangered snouted crocodiles until construction was completed, and waiting months when construction was forbidden to prevent destroying a bird species that was nesting. Plans had to respect MDB standards and took a considerable amount of time and work to complete.

But the results were positive; the crocodiles in question, according to Mandaba, could hardly coexist with the local population who see such an animal as a threat, especially to children. A night catch was organised in coordination with the Ministry of Environment to rescue the crocodiles found in the project area and park them at the zoo during the construction period. The crocs will be released downstream in a protected area where they will be able to grow and reproduce far away from human settlements, affording better protection for both populations.

The next big thing?

Mandaba is bullish about the future of private small hydro and believes private investment can propel efficiency. Where the public sector seeks out large dams (50MW or more), private investors tend to go small. These projects consequently have a smaller impact on the natural landscape, reducing upfront costs. “We take the design of the public sector and we usually just reduce it because you don’t need such a big dam,” says Mandaba. For Themis’ project in Madagascar, though the expected capacity is 200MW, the reservoir is five times smaller than the Bandama river, instead relying on a 700m high drop from a mountain. Another project in Togo is much smaller, taking an initial dam of 60MW and dividing it into two 25MW dams. “By dividing into small dams, we divide the size of the reservoir – if you reduce the size by five, it will flood five times less and displace five times less people”.

Chatterjee is similarly advocative of smaller run-of-river hydro projects from a development perspective. “Power is very skewed in the cities and it’s very expensive to get electricity access to rural communities … the small hydro’s in Uganda that we have invested in do exactly that, they balance out the grid”. While large hydros can be transformational, they are very complex and require a lot of design work – 10-20MW projects are much easier to implement over a shorter period of time.

On top of hydro projects, there is also an opportunity to install five 5-10MWs of floating solar. Projects have to assess the level to which the dam rises and falls and then whether anchoring floating solar will be possible, but Mandaba emphasises the relatively easy additionality of the effort: “When you have your dam, the transmission line is there, the land is already acquired, and it’s just logical that you have to maximize the use of land … it’s very little additional work”.

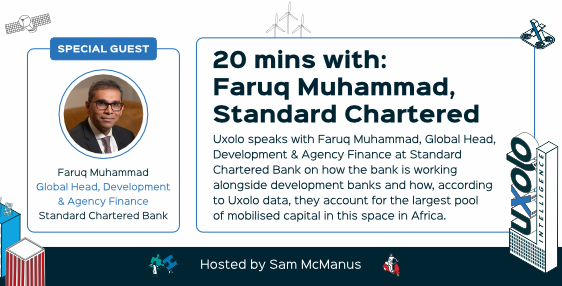

The Uxolo perspective

Despite the length of time and macroeconomic pressures the plant faced reaching senior close, the foundations of the Singrobo-Ahuaty project were strong from the outset.

It was initially developed by the local sponsor, IHE, which was familiar with the country’s energy sector and grid, and the government had already identified the dam as a potential site for hydropower. The shareholders were well versed in hydropower construction, and knew to avoid the fate of similar projects that did not secure initial funding sufficient enough for construction - like Senegal’s Dakar airport where the bridge loan was not sufficient to complete construction, and had to be renewed several times, causing delays and consequently cost overruns.

For Chatterjee, Singrobo represents a “model for paving the way for more hydro IPPs in Cote D’Ivoire and in the sub-Saharan region”. But as she stresses, this project and future hydro IPPs require “open-mindedness” as well as the ability to be “nimble and adaptive” when faced with complex construction designs and considerations, and volatile markets.