Will emerging markets always be the markets of the future?

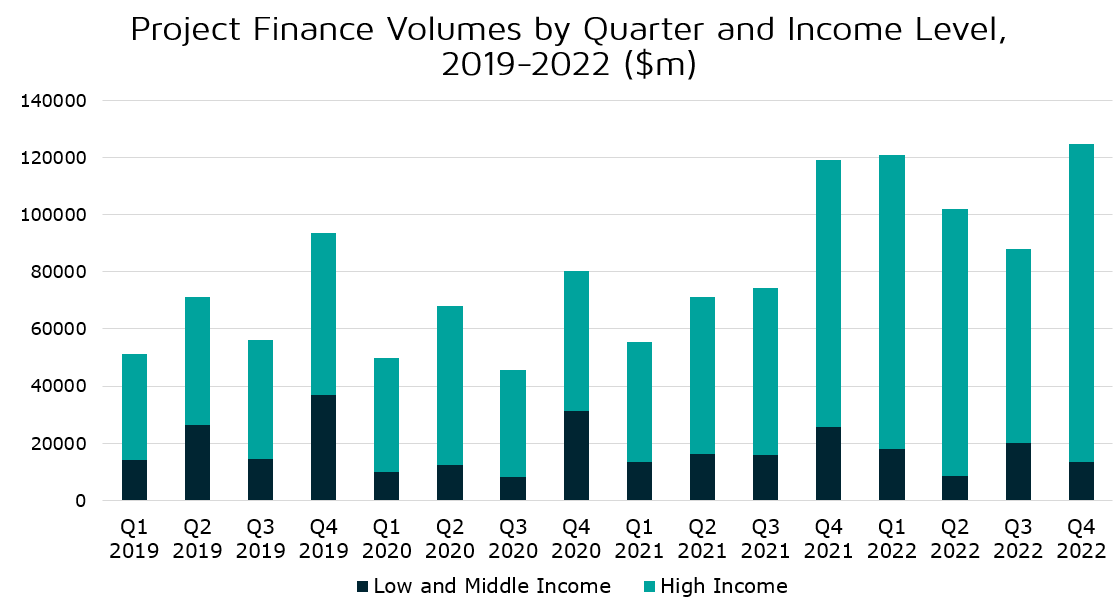

Despite DFI emerging markets support, global project finance deal flow has skewed heavily in favour of high-income countries over the last two decades, and the gap between developed and emerging markets has grown wider since 2019. But does the energy transition point towards an eventual equalisation?

Since the end of March, Uxolo’s sister publication Proximo has been polishing its 2022 full year data ready for release later this month. Initial findings point to a continuation of the upward trend in global financing volumes and a modest improvement in transaction numbers. But a more troubling trend is that emerging markets volumes have not shared in this improvement since 2019.

In fact, volumes of project financings in countries classified by the World Bank as low income and middle income reached their lowest level yet in 2022. After hitting $91 billion in 2019, they slumped to just over $61 billion in 2020, and recovered a little in 2021, before falling back to just under $60 billion in 2022.

Source: Proximo Intelligence

Source: Proximo Intelligence

Project finance structures and techniques are perhaps uniquely suited to working in emerging markets. The use of a suite of contracts and credit enhancements to allocate and minimise risks on a project financing is particularly important in markets where political and economic risks are higher and financial markets are less developed.

But while in the 1990s big ticket emerging market power projects dominated project finance, the story this century has been of large greenfield and brownfield transactions in high-income economies. This trend has only accelerated as financial sponsors, most of them with a strong OECD bias, moved to the forefront of the project finance market.

But this recent poor performance suggests that there may be more urgent issues to consider. One popular explanation is that emerging market governments have lacked the ability to maintain procurement efforts at the same time as dealing with the aftermath of Covid and the impacts of higher commodity prices on their fragile economies. Another is that higher interest rates have increased the risk premium that investors in developed markets will require for investing cross-border into middle and lower income economies.

Both explanations have one chief issue, and that’s the lag that is typical between investment and procurement decisions and financial close. The small bump in activity in 2021 might represent pent-up financing activity from the pandemic, but any market weaknesses may not have had time to feed through into financing activity. And those cross-border investors have long been quite averse to making big commitments to emerging markets. Local corporates are becoming more central to project financings in middle and lower income economies, though they are very vulnerable to liquidity pressures.

One other fashionable culprit is a lack of financing capacity at development finance institutions (DFIs), which have struggled to meet the challenges of the pandemic, but are more generally thought to no longer have the ability to respond to the demands of climate change. Solutions put forward by their critics include tweaks that DFI shareholders could make to allow them to put more cash to work. Uxolo has looked in detail at a number of proposed solutions – from callable capital to hybrid capital bonds.

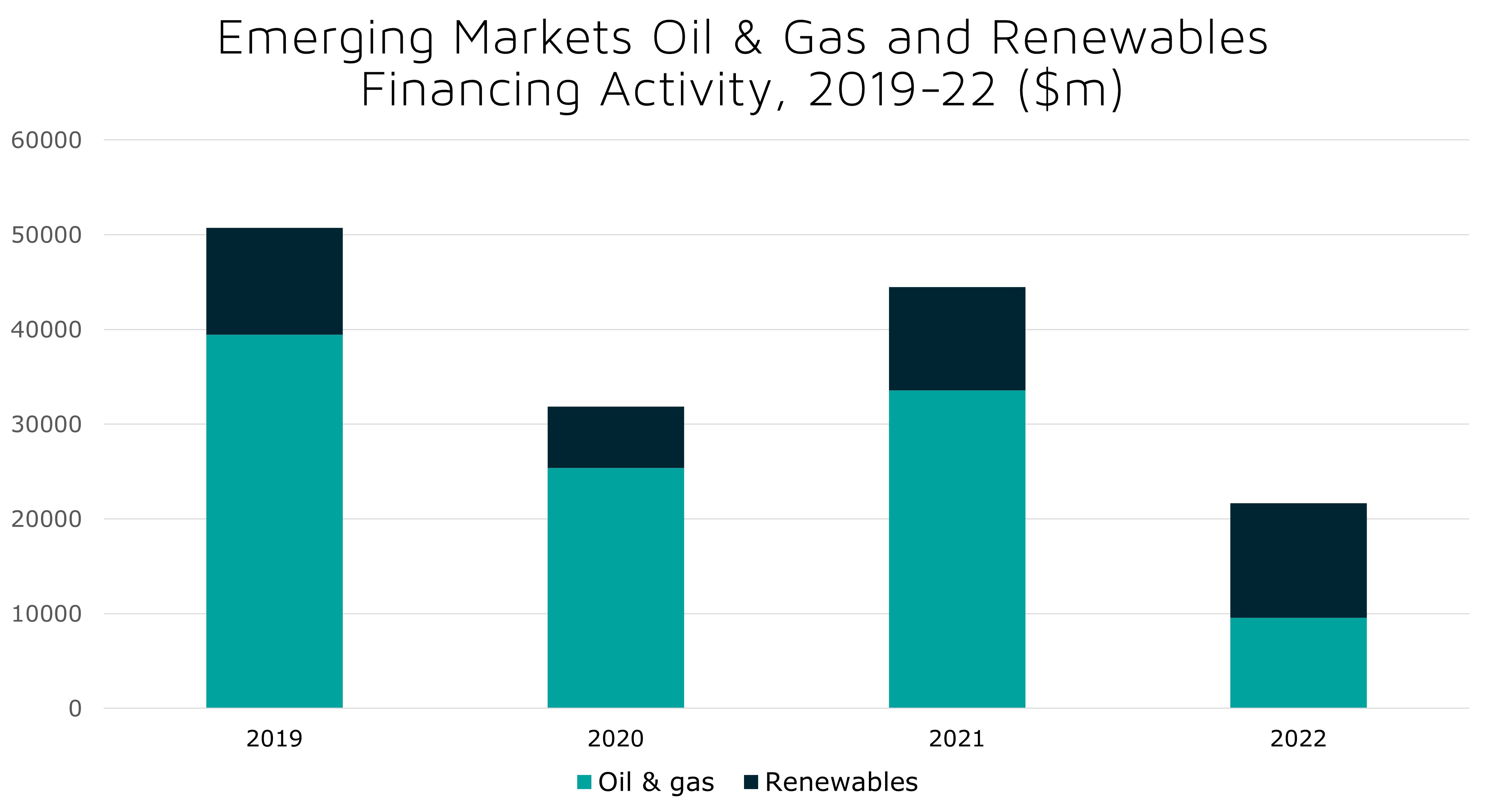

But the main culprit is probably a little bit more prosaic: Emerging economies are still highly dependent on extractive industries, and particularly oil and gas. Some of that relates to governments feeling flush enough to make commitments to long-term infrastructure concessions, even if that is really not the way governments should be making infrastructure investment decisions.

But more straightforwardly, large mining and oil & gas projects completely dwarf the smaller volumes attributed to very worthy investments in renewables and transport and social infrastructure. With the recent falls in oil & gas volumes, emerging markets are looking superficially much more subdued.

And there lies the good news. Because overall emerging markets transaction numbers are very slightly up, from 227, to 230. This means that average deal size is down, from $310 million to $260 million. While oil & gas volumes are sharply down, renewables volumes are just a little bit up between 2021 and 2022.

Source: Proximo Intelligence

This larger number of deals means that in general more bankers might be employed putting together deals in emerging markets, and that probably bodes very well for the growth of the product outside high-income countries. It will mean that sponsors will have to keep an eye on transaction costs, which can easily overwhelm the affordability of smaller projects. But this time, the future of project finance might really be in emerging markets.