Talking shop: IDA's under the radar initiatives

Of the World Bank Group’s lending arms, IBRD, IFC, and MIGA are familiar names to most financiers. But IDA is less often in the press, despite its critical development role and the controversy it occasionally garners. Uxolo talks to Enrique Blanco Armas, manager of the IDA’s strategy and operations team, about the bank group’s oft-overlooked initiatives.

The World Bank Group’s (WB) lending arms – the IBRD, IFC, MIGA, and IDA – operate in different spheres with different capacities and purposes. But there are plenty of overlaps – as the initially controversial Private Sector Window (PSW) demonstrated.

In 2016, as part of the IDA’s eighteenth replenishment of resources (IDA18), the WB group decided to create a $2.5 billion IDA-IFC-MIGA PSW, which aims to catalyse private sector investment in IDA-only countries – but in reality has entailed IDA funding being redirected to IFC and MIGA financings. Criticism of the scheme was loudest during the Covid-19 pandemic when the window had a remaining $1.4 billion and, of this amount, only $865 million was reallocated to IDA’s Crisis Response Window (CRW).

Of the remaining capital, PSW’s biggest loans in 2020 were directed to a $215 million working capital solution for IFC’s existing clients; $250 million in unfunded guarantees for a trade financing programme; and $40 million for the Currency Exchange Fund (TCX), which IFC owned 4.49% of and benefitted from member-pricing.

The preference for supporting private finance, with very little evidence these projects would reach the poorest and most vulnerable, seemed out of kilter with IDA’s mandate – 'concessional loans and grants to the world's poorest developing countries'. More recent projects have been more focused on IDA’s core role, as Enrique Blanco-Armas illustrates: “We have been able to introduce some landmark innovations with PSW deals, such as the first ever local currency bond in Cambodia and the first SME targeted private equity fund in the Kyrgz Republic”.

While the PSW remains a topic of discussion, the release of the CRW+ has been praised as being more in line with IDA’s real responsibility and purpose: extending development financing to the most vulnerable. The new facility aims to augment IDA’s emergency funding and provide new resources for Ukraine and Moldova, and donors should see the benefit of propping up the demand driven by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, especially as the existing window is expected to fall short. Whether the new facility receives the donor support it needs will certainly be a priority for Ajay Banga’s incoming premiership.

In conversation with... Enrique Blanco Armas

Uxolo: What is IDA’s role within the development finance system and what does that look like?

Enrique Blanco Armas (EBA): IDA was established in 1960 to reduce global poverty by providing zero to low-interest loans, called credits, and grants for programmes that boost economic growth, reduce inequalities, and improve living conditions.

We are the largest source of concessional financing in the world and we’re stable – countries can use us to plan ahead many years in advance. We facilitate individual Country Partnership Frameworks with governments, tailored to each nation's development priorities with an emphasis on country ownership and sustainable outcomes. About two-thirds of IDA's funding is allocated through this country-driven model via non-earmarked funds or direct country allocations.

The remaining third of disbursements is allocated through ‘windows’ – prioritised areas agreed upon with donors and borrowers which have a thematic focus. For example, we have the Crisis Response Window which aids countries dealing with natural disasters, the Window for Host Communities and Refugees help with refugee situations, and there is also the Regional Window which supports regional projects.

Uxolo: What locations and environments do you primarily operate in?

EBA: IDA operates in a total of 75 countries, of which 39 are in Africa. Countries are eligible for IDA resources on the basis of relative poverty and their lack of creditworthiness for IBRD borrowing, with exceptions made for some small-island states due to their vulnerability to shocks.

Countries at a high risk of debt distress or already experiencing this receive 100% grants; countries at moderate risk of debt distress are eligible for 50-year credits (with a grant component of up to 73%), and those at low risk of debt distress receive credits with a grant element of 53%. A grant element of 73% means that, in real terms, for every $100 that we provide the country, they return $27.

We undertake a mix of long-term development programmes and reactions to crises. A good example of this is the Covid-19 pandemic; we obviously stepped in with immediate crisis support for many countries under the Crisis Response Window, but we have also been active in providing longer-term funding to support countries in strengthening their pandemic preparedness, for example with the $147 million Regional Disease Surveillance Systems Enhancement Program in Central and West Africa. Since 2017, we have been working with countries to understand some of the key constraints they would have when faced, which came right in time to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Uxolo: What are lending expectations like – would you say the IDA expects a return comparable to that of other DFIs or does it expect losses? How do you ensure a sustainable balance sheet in this environment?

EBA: Projects funded by IDA have long gestation periods and focus on a diverse variety of development areas. Loan maturities can range between 30-50 years depending on the risk of debt distress, so naturally it can take a while for these projects to generate returns. Although, it is most important to note we measure our returns not only in dollars but in development outcomes too.

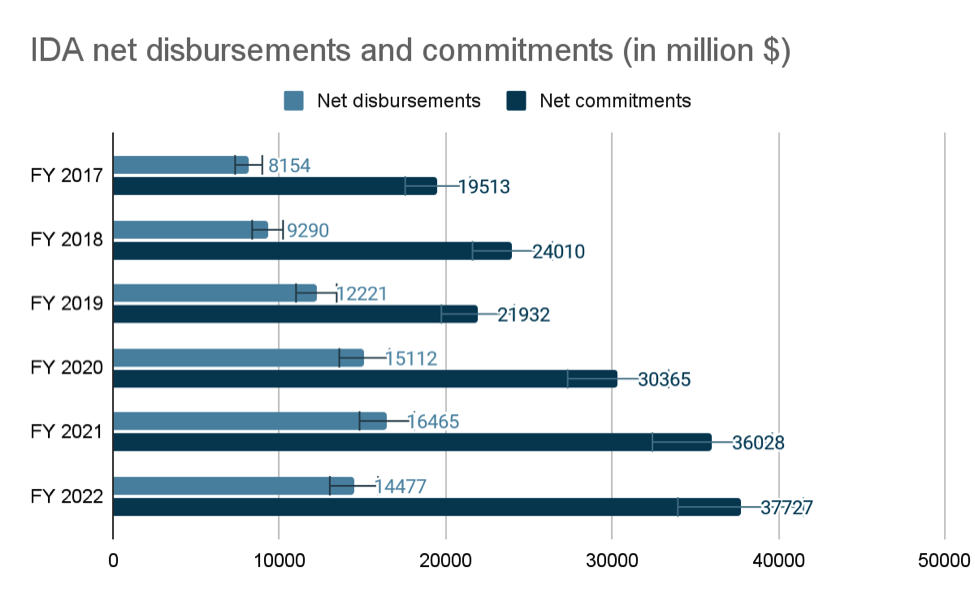

We are very active in managing our balance sheet better. First of all, to be able to provide the type of financing we do, we work together with donors and borrowers’ representatives and, every three years, replenish our resources and review the policy framework. At the most recent occurrence in 2021, called IDA20, the bank put together a historically large $93 billion financing package to power its lending for 2022-2025 which was backed up by $23.5 billion of donor grants.

With IDA20, we also introduced a range of balance sheet optimisation measures including two new financing terms. The 50-year credit tenors are new and replace the 50/50 mixes we used to employ (50% grants and 50% regular IDA credits). While the grant element is almost the same, this new type of tenor is a much better use of our balance sheet, and has provided us with additional volumes available to countries.

We also introduced shorter-term 12-year maturities with six-year grace periods where there is no interest and no service costs. We provide these only to countries with limited debt vulnerabilities in order to provide them with higher financing volumes.

It was also with an innovative financing model that we brought in in 2018 that we have been able to combine our donor contributions with reflows from past IDA credits as well as market borrowing. As the market has gotten to know us better and we have gotten to know the market better, we have been increasing our issuance of long-term bonds.

Our last issuance was in 2022 with a 15-year Sustainable Development Bond that raised €2 billion, with an annual coupon of 1.750% and an issue price of 99.752%. That transaction built on our efforts to extend our yield curve, and 73% of the buyers were made up of institutional investors – a 10% step-up in demand from this group compared to the previous €2 billion issuance that offered a 0.70% coupon in January 2022.

Source: IDA Financial Statements

Uxolo: How do you mitigate, and perceive, risk in the riskiest of landscapes?

EBA: I will try and answer this in two ways: first, from an operational point of view and then from a financial view, as we have a number of tools that we use to help mitigate risks. First we have the crisis response window, which received a $3.3 billion replenishment at IDA20, that supports countries with natural disasters, pandemics, and severe economic crises. The window has, among other disasters, supported the Yemen famine crisis, and countries in Southern and Eastern Africa with the severe floods.

In July 2023, we approved a new crisis facility, the CRW+, which we are using to raise additional financing to help countries deal with the accumulation of crises many are facing. The facility is aiming to raise $6 billion from existing shareholders with a due date in December 2023.

We also have the Private Sector Window, an innovative tool used to mobilise private investments in the poorest and most fragile IDA markets by transferring some of the risk from IFC and MIGA’s operations. We blend concessional funds with private sector investments, in the aim of mitigating several risks like currency devaluation, currency risk, and political risk. I would argue that we have been successful with the window as we have raised about $18 billion for the most vulnerable markets with just $3.9 billion of that being IDA resources. We have been able to introduce some landmark innovations with these PSW deals, such as the first ever local currency bond in Cambodia and the first SME targeted private equity fund in the Kyrgz Republic.

On the financial side now, we apply a comprehensive risk management framework to protect IDA’s balance sheet and its financial interests. That includes monitoring and controlling our market credit, ensuring we can defend our triple-A rating, and maintaining our relationship with our donors. Our donors have always stepped up for us: the most recent example is when we shortened the IDA19 cycle from three years to two. We were able to provide $16 billion in additional financing to our clients during the Covid-19 pandemic as a result.

Uxolo: What types of institutions primarily operate in this space? What collaboration do you do with the private sector and with other public institutions? How transparent is the sector?

EBA: Partnerships are central to IDA’s work at the country, regional and global level. We work very closely with UN agencies on all three of these levels, on health, on refugees – on pretty much everything. We also work very closely with the IMF on macro-monitoring and debt issues – when you asked how we can manage risk in the riskiest of landscapes, some of that ability comes from working very closely with the IMF and having that assessment of debt sustainability in all countries.

We also work very closely with MDBs, the European Commission, and bilateral partners. We have coordination platforms in most countries and that is also helped by our strong country presence in most areas. We have large lending capacities in most countries, but we also have fairly active knowledge and analytic work which inform our policy dialogues too. We can co-finance with bilaterals and multilaterals which allows us to mobilise additional funding for countries; although most of our financing goes through local and central governments.

We help governments establish effective implementation arrangements with their key partners, such as local CSOs, and these relationships are particularly important in situations of fragility, conflict and violence where maybe our ability to operate is more constrained. For example, in South Sudan, Yemen, and Afghanistan, we work primarily through UN agencies and international CSOs.

Uxolo: What’s in the pipeline for IDA?

EBA: The G20 Report on MDB Capital Adequacy has catalysed discussion of stepping up IBRD and IDA’s balance sheets to help countries meet their huge financing needs, with climate change, debt crises, and civil fragility. We have now also engaged in the evolution process which will allow the World Bank to become a better and bigger bank that is fit for purpose to respond to the most pressing needs of people and the planet. As one of the institutions of the World Bank, IDA will be subject to whatever the group decides to change in light of this process.