Too high a price

Africa pays a premium for its debt that in many instances it should not. Why the onerous debt costs? And what can be done about it without major systemic change?

How much should debt cost for sovereign borrowers in a region with the smallest public debt (just 2% of the $97 trillion global public debt pile), the highest MDB/DFI recovery rate (83.9%) from contracts with private counterparts according to GEMs, and average debt-to-GDP of 65% (Asia and Pacific is 93.7% according to IMF data)?

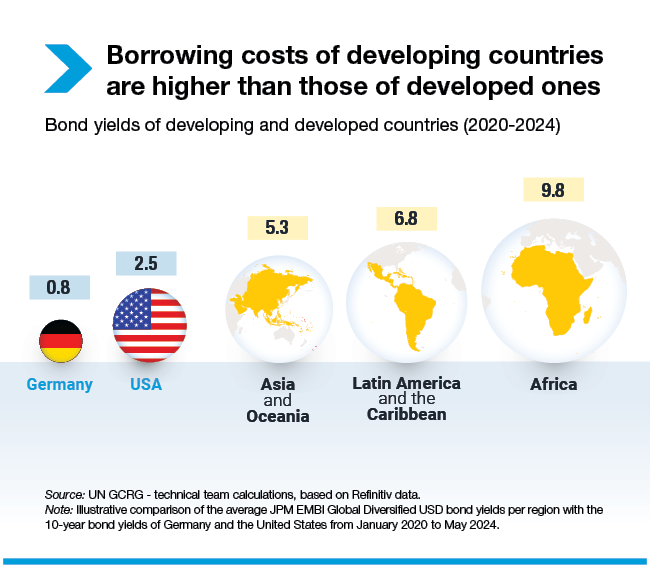

Based on those statistics in isolation – a little less or around the average 5.3% US dollar bond yields Asia and Oceania have been paying from 2020-2024 would seem about right. But the economic vital statistics quoted above are for Africa, where anything beyond 60% debt to GDP is not considered sustainable, in part because Africa pays so much more than any other region for its debt.

The difference in cost of African debt is considerable, even for its two investment grade rated countries Mauritius and Botswana. According to figures from UNCTAD the Africa premium on JPM EMBI global diversified bond yields is almost 5% compared with Asia and Oceania, and a staggering 9% more than the 10-year bond yield of Germany.

The AfDB estimates that with Africa’s total external debt at $1.152 trillion at end of 2023, the region will pay out $163 billion just to service debts in 2024. Put that in the following context – according to Uxolo Data MDB/DFI loans (approved and closed) to Africa in 2023 were around $58 billion, $105 billion less than Africa’s total external debt interest payments this year – and a bigger problem emerges: is MDB/DFI debt across the whole African debt mix indirectly cross-subsidising more expensive external borrowings from the private sector?

A 2023 dataset from the Kiel Institute’s Africa Debt Database concluded it very likely is – along with taking the interest edge off Chinese development loans, which average 3.2% interest and are more expensive than the 0.5% ODA loans from Japan, the 1.7% from France and Germany and the 1% from the World Bank.

According to Professor Christoph Trebesch, research director and debt researcher at Kiel Institute: “In the last 20 years, African countries have recorded very high growth rates, on average, and the demand for capital has strongly increased too, for example to finance the construction of basic infrastructure. Yearly sovereign debt issuance has risen from around $10 billion in the early 2000s to around $80 billion between 2016 and 2020.

“Government bonds issued on the international capital market and Chinese loans played only a minor role in the 2000s, but were then largely responsible for the African borrowing boom from 2008 onward. In some years, these two creditor groups account for a quarter or almost half of African sovereign borrowing.

“Numerous countries, such as Egypt or Kenya, are simultaneously borrowing money both from private investors and, on a large scale, from public lenders, so that the low-cost loans from the public sector – ultimately taxpayers' money – are being used to cross-finance the high returns of private investors such as hedge funds."

Risk perception

The reasons Africa is paying so much more for its borrowing from the private/commercial sector are many. But broadly speaking they boil down to subjective risk perception and lack of secondary markets for African debt.

When it comes to inflated risk perception, the whole international financial market – including the ratings agencies, African borrowers and governments, MDBs and DFIs – share some responsibility through their inaction on improving data gathering.

In 2023 a UNDP report focused on the lack of sufficient hard data on African economies and the resulting subjective components included by global rating agencies in assessing the risk of lending to Africa. The conclusion of the report was stark – in purely monetary terms, subjectivity in credit ratings costs African countries (for which data was available) $28 billion in excess interest and more than $46 billion in lost borrowing opportunities. The numbers combined are nearly 12% more than all of Africa's net official development assistance (ODA) in 2020 according to UNDP.

Various solutions to the ratings subjectivity issue have been proposed: establishing alternative operational models for credit rating services, although that would require regulatory reform at both the international and African continental levels; and establishing an MDB ratings agency or a pan-African ratings agency. The common thread to all proposals is the need for more data on which to base ratings, and on that front the much-vaunted improvements to the GEMs database – which certainly illustrate that African ratings are very likely often out of kilter with the risk reality – are not going to have a significant impact given the lack of granularity in the data.

Reducing the cost of sovereign debt

But within the existing global financial system, there are initiatives underway that could cut the cost of African debt without the requirement for systemic change.

The UNECA Liquidity and Sustainability Facility’s (LSF) debut $100 million African sovereign eurobond repo deal, announced in late 2022, was one such initiative – and it has since been followed by another LSF $100 million repo with ADIA in late 2023.

For those with a fleeting knowledge of repo, the money market instrument is basically a short-term (normally 24 hours but can be up to a year) collateral-backed interest-bearing loan. The borrower sells securities it owns to a lender and agrees to repurchase those securities later at a higher price. The securities serve as collateral for the repo loan. The difference between the securities’ initial price and the repurchase price is the interest paid on the loan.

The LSF facility functions in the same manner – it is a commercial platform with no concessional rates. In its debut $100 million repo, the LSF had Afreximbank as funding donor for a loan raised against a basket of sovereign Eurobonds from Egypt, Kenya and Angola owned by Citibank. The Citi collateral generated a repo loan at 65bp over SOFR.

Repo is the liquidity back room engine of developed markets – but no such capacity exists for African bonds and as a consequence investors ask for a high yield on African bonds as there is no other earning capacity from the paper.

The idea behind LSF is that a well-functioning secondary repo market will boost liquidity in African sovereign bonds, making these assets more attractive to investors who will therefore demand lower bond yields. Estimates vary but according to David Escoffier, CEO of the LSF Secretariat, potential savings to African governments of $11 billion over five years are “very real figures.”

Escoffier wants to ”get rid of the liquidity premium that is imposed on Africa and also the perception premium… Everybody is entrenched because when you have a bond that's yielding 12%, you don't really want this to change if you don't have to.

“So, there are a lot of things that do not change just because there is no incentive for change. And that's exactly what we are trying to do, to be the actor of change, but in a self-sustainable way, not taking resources from other development pockets, just making the markets do what they do best – trade.”

LSF needs to be the spark that generates a full-blown African repo market, a market in which LSF is reduced to the role of backstop and commercial banks take the leading role.

While that ambition will likely take some years the LSF is very much a deal pipeline rather than pipe dream: The LSF currently offers refinancing of 120-plus eligible African sovereign Eurobonds for maturities of up to one year, and is looking to increase its counterparties to around 20, with an optimal eventual funding capacity of $30 billion.

Facilitating more project bankability

In addition to reducing the cost of African sovereign debt there are also calls to facilitate the bankability of more standalone non- and limited recourse project debt in Africa.

Commodity linked project financings with dollar-based income streams and highly creditworthy international sponsors rarely have trouble with bankability. But for SMEs and social infrastructure projects it is a different story – local income streams necessitate hedging unless borrowing in local currency, which may not be an option if the project costs are in US dollars or euros.

In 2021 the OECD introduced a temporary common line, which allowed export credit agencies (ECAs) to cover up to 95% of the total export contract value on sovereign transactions in the OECD risk categories 5-7. The common line reduced the 15% down-payment that borrowers needed to find for export finance transaction to 5%, thus facilitating more deals and often enabling the borrower to fund the down-payment from internal resources rather than a lender.

The 15% down-payment has been a longstanding hurdle to deal flow in Africa, so much so that Acre Impact Capital started to address the same problem with the launch of its Export Finance Funds in 2023.

The OECD common line temporarily eased the problem, and although it was extended last year to 13 December 2024, there is still no long-term certainty. And certainty is what is required given, as Gabriel Buck, founder of consultancy GKB Ventures says, “the need to have the export credit agencies go to 95% is a real necessity at a sovereign level in Africa”. A permanent 95% arrangement could make a major difference to African project facilitation and hence volume closed.

The Uxolo perspective

The cost of African debt clearly needs a rethink, along with the measurement of risk and perception of risk. Even with MDB reform likely to up lending budgets considerably, Africa will still be competing with developed markets for MDB/DFI liquidity, so private sector debt will still be tapped and the onerous cost of it will still be an issue – not least because of the MDB/DFI cross-subsidy that the Kiel Institute’s research points to.

The beauty of initiatives like LSF and the OECD common line is that they do not require vast systemic change and also don’t tap into the existing concessional finance budgets of DFIs and MDBs. Change without short-changing has got to be the way forward.